Miniatures Amplify a Story of Horror

Pauline Kalker, a founder of the Dutch theater company Hotel Modern, never uses the word toy when referring to her company’s work ‘Kamp’, a 36-by-33-foot model of Auschwitz populated by 3.000 three-inch-tall figures. ‘The word is not in our vocabulary,’ said Ms. Kalker in accented English in a telephone interview from Spain, where the group was on tour. ‘We are making a live animation film on stage.’ Yet ‘Kamp’, which mixes theater, music, video, sculpture and puppetry, is scheduled for six performances this week starting on Wednesday as part of the Toy Theater Festival at St. Anne’s Warehouse in Brooklyn. The festival celebrates miniature and puppet theaters, a popular 19th-century art form, from around the world. Ms. Kalker and her partners Arlène Hoornweg and Herman Helle arrived in New York over the holiday weekend to set up the ‘Kamp’ scale model, a process that typically takes two days.

The 1986 publication of ‘Maus’, Art Spiegelman’s acclaimed graphic novel, in which Jews were portrayed as mice and Nazis as cats, helped pave the way for Holocaust stories to be told in genres that once might have been seen as too idiosyncratic or irreverent. Ms. Kalker said that after mounting a critically acclaimed 2001 show about World War I that featured miniature figures, she realized that the company could approach Auschwitz similarly without lapsing into cliché. ‘Our medium had a special way of telling the war theme,’ she said.

Mr. Helle, who designed the models, said he started with one figure and one barracks. ‘We didn’t know exactly what story we could tell,’ he said. He then made 100 puppets, but the three partners realized that was not enough. He made 300; still not enough. Even after making 3.000, he said, they recognized they could only present a fraction of the total picture. The small figures are made of wire with heads of Plasticine, a clay that hardens when baked. The expressions – from poked in eyes, noses and mouths – are frozen in Munch-like howls. The prisoners wear black-and-white-striped cloth. For the guards and the new trainloads of arrivals, Mr. Helle photocopied old photographs, cut out the clothes and hats and glued them on. ‘We were looking for an easy and fast way to make them,’ he said. Mr. Helle made the translucent bodies of the naked, gassed prisoners out of hot glue that melted around wire frames. ‘It makes them look very vulnerable, ‘ he said. About 10 visual artists helped with the models. The whole projects took about eight months to construct. The complete installation, made mostly of plain gray corrugated cardboard, includes barracks, guard towers, crematoriums, gas chambers with buckets of gas pellets, a dining hall for the gueards, a train and tracks, and the notorious gateway sign, ‘Arbeit Macht Frei’, ‘Work Makes You Free’.

At performances of ‘Kamp’, the three artists move the figures around the set. The tiny puppets sweep, shovel rocks and line up to be counted. Prisoners are beaten and executed by hanging; others are gassed; corpses are buried or burned. Using a small camera, Mr. Helle films the figures in a tight frame, projecting the images in close-up on the wall of the theater. The audience is seated around the model, as if looking down at the camp from a mountainside. ‘All the time you have an overview,’ Ms. Kalker explained, ‘and with the camera, we give you an insider’s view of what is happening in the camp. We want to make the audience eyewitnesses.’

Hotel Modern experimented with different methods of storytelling. The artists tried working with a script. One idea was to have a Mengele-like doctor performing medical experiments. ‘It didn’t work at all, ‘ Mr. Helle said. ‘It was too much like a history lesson.’ Another idea was to have a group of women talk about food and cooking, or have a Nazi official visit. Those proposals were also scrapped. The nearly hour-long show has no dialogue, but there is sound from small microphones, which amplify the sweeping, and from the miniature railway, as well as added recorded effects that include the sounds of wind, swallows, industrial clanging and a screeching squeak from a cart that Mr. Helle taped while visiting Auschwitz itself.

Ms. Kalker, whose grandfather died at the camp, said she invited Holocaust survivors, including her cousin Ralph Prins, a sculptor, to see early versions of ‘Kamp’. ‘I asked him to see it, if he thought it was appropriate,’ Ms. Kalker said. ‘We wanted their approval,’ she said of the survivors. The work has received good reviews, except in Germany, where ‘Kamp’ provoked a mixed response. Ms. Kalker said she thought Germans were still figuring out how to deal with this part of their history. Critics complained that ‘using puppets was making it seem banal, ‘ she said, or they thought ‘it was in bad taste.’ Responding to that point, she noted that Auschwitz and other camps have miniature models of their original layouts today in their visitors’ centers.

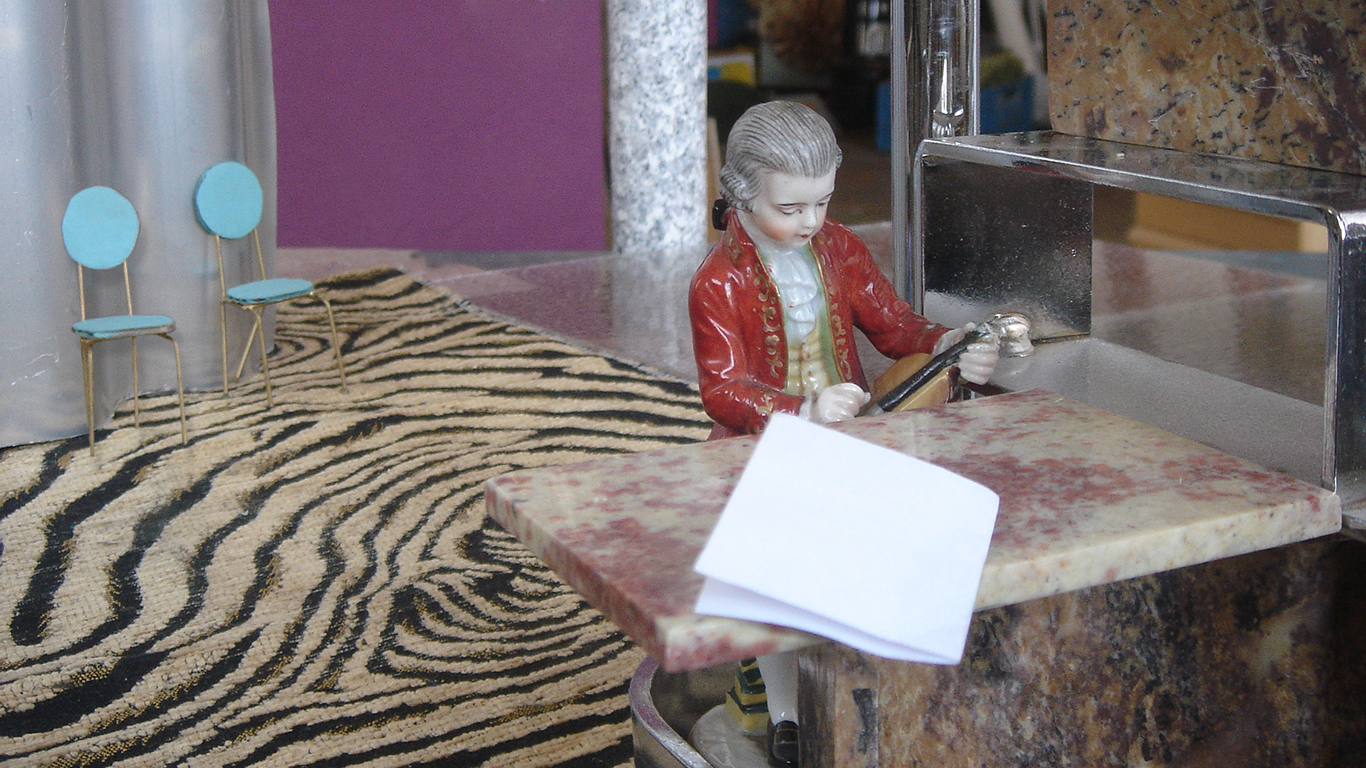

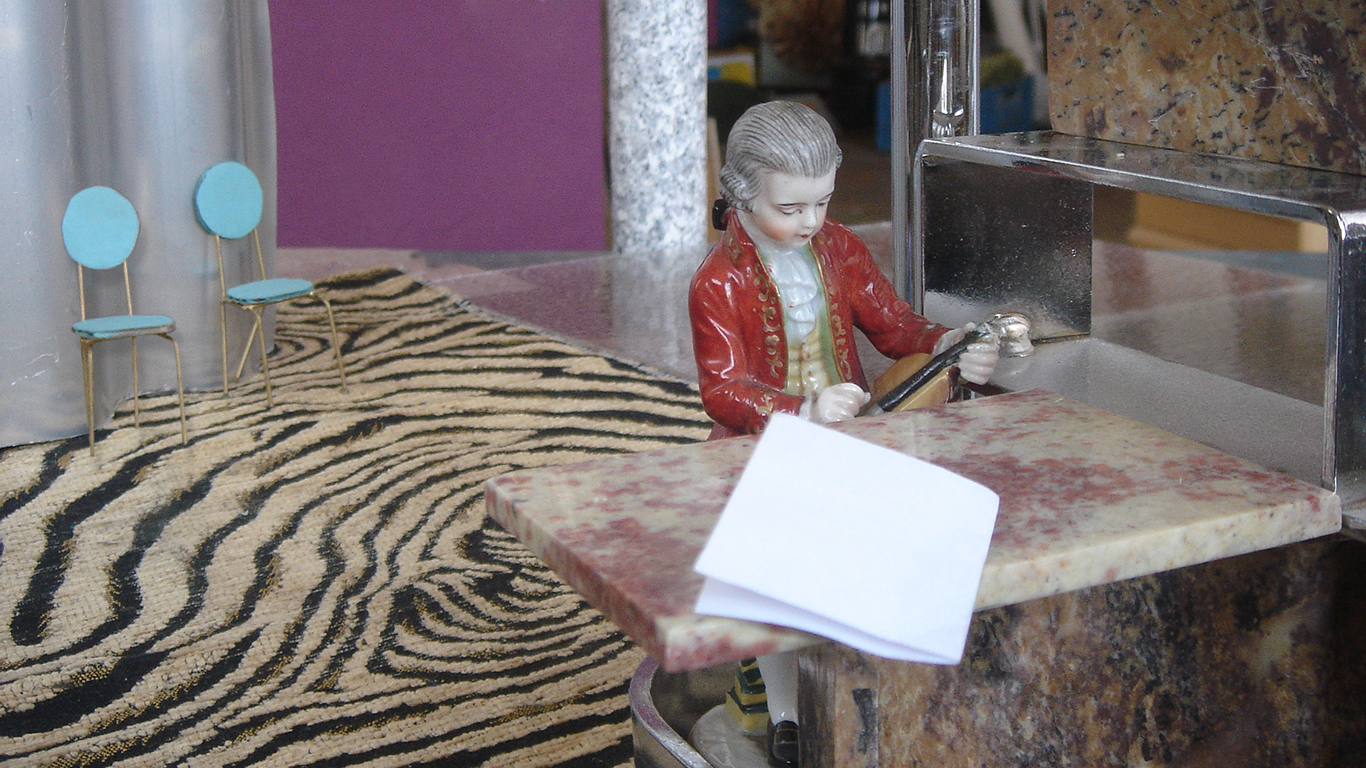

For their performances in Spain last week, Hotel Modern showed a different piece, called ‘Shrimp Tales’. It is a comedy starring 400 prawns, who play human beings eating in restaurants; attending church, a wedding and a funeral; playing the piano; boxing, giving birth; performing surgery; lining up for an episode of ‘Antiques Roadshow’; and landing on the moon. ‘We have a humorous side,’ Ms. Kalker said. ‘I would not want to perform only ‘Kamp’.

01-06-2010