An explosive miniature recreation of The Great War (interview)

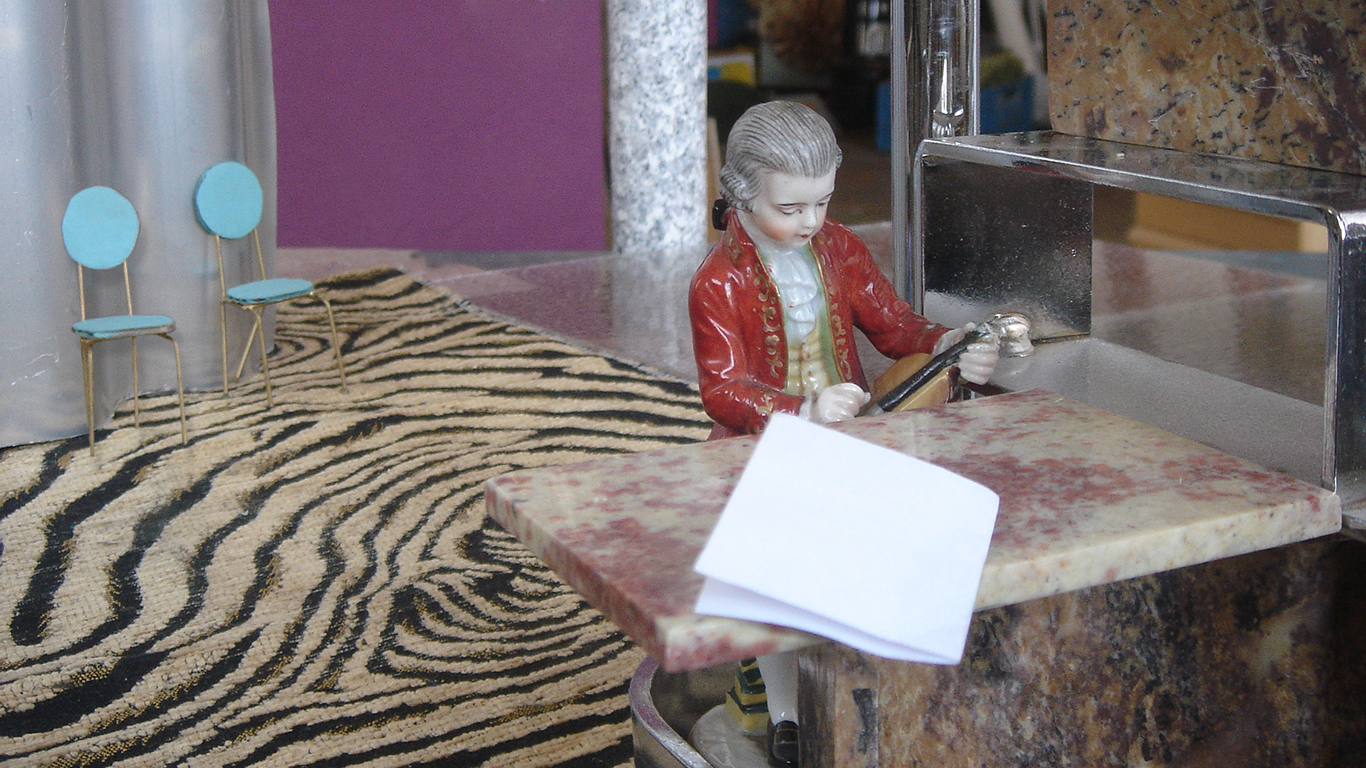

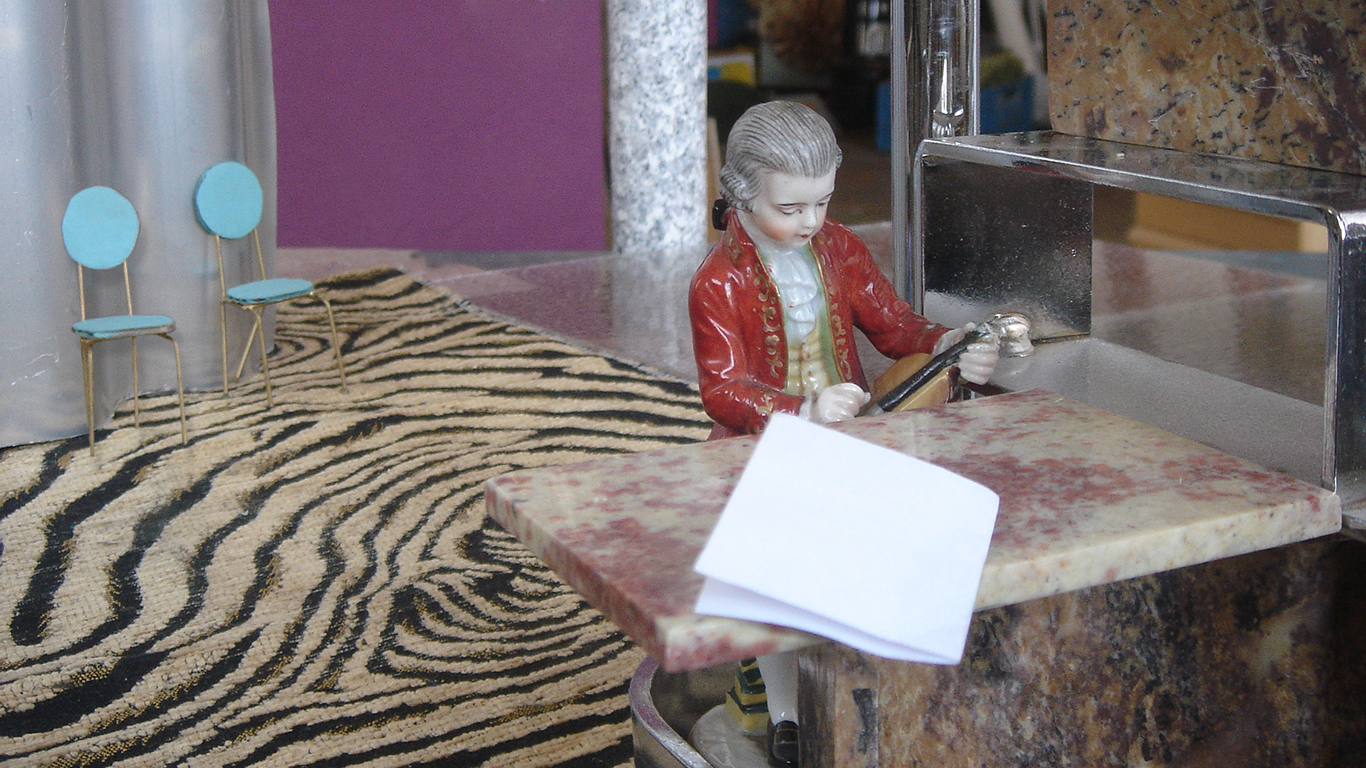

Toy tanks, Action Man figures, parsley, potting soil and powdered sugar are among the miniature props and everyday items used to recreate the horrors of the battlefront in Dutch live-animation company Hotel Modern’s 2018 Adelaide Festival show The Great War.

Hotel Modern made an impact at the 2013 Adelaide Festival with Kamp, a portrait of a Holocaust death camp, and The Great War – which draws on the real-life experiences of World War I soldiers – is said to be equally as powerful. In The Great War, puppeteers Herman Helle, Pauline Kalker and Arlène Hoornweg re-create scenes from the Western Front in a miniature set, with the action projected onto a large screen and accompanied by a soundtrack of live sounds created by composer and Foley artist Arthur Sauer. It is being presented at the Festival on the centenary of the armistice that ended World War I. “At this significant time, it is artists who best bring to life what the experience meant for ordinary soldiers on the front line of battle, and Hotel Modern has achieved this with stunning force and immediacy,” says Adelaide Festival co-artistic director Rachel Healy.

Below, Kalker, Helle and Sauer tell InDaily what they wanted to achieve with The Great War, and explain the ingenious ways they have managed to replicate everything from trees and snow, to explosions, smoke, and the sounds of machine guns and tanks. The Great War was adapted from interviews with World War I veterans, as well as the diaries and letters of soldiers.

What are some of the common themes of their accounts which the production conveys? Pauline Kalker: “We focus on the question what war is like for the people who are in the middle of it. We wanted to show the experience of the soldiers who fought in the trenches – what it was like to be a soldier in this war, in which so many horrible weapons like machine guns, poison gas and tanks were used, often for the first time in history. We were looking for detailed practical descriptions, like what did they see, hear, smell, feel; what was their daily life like. We also focused on what happened mentally, how the act of fighting and killing affected them, how they dealt with injuries and the death of their mates.

I understand the production draws on the letters of one particular French soldier, which were discovered decades after the war ended. Who was he and what happened to him? Herman Helle: “His name is Prospert. A friend of us had bought all Prospert’s letters, written to his mother during the war, in a secondhand bookshop in France. They cost a fortune. When the shopkeeper explained that was because of the fieldpost stamps on the envelopes, our friend took the letters out of their envelopes, and got them for a more or less symbolic price. We don’t know much about Prospert, apart from his name, that he had a sister, and that he used to live in Toulon, France. He wrote hundreds of letters – they all begin with “Chère Maman” (“Dear Mother”). In the beginning, his handwriting is almost childlike; during the war it develops and becomes more experienced. He loses his best friend, but survives the war, and his last letters (which are not in our show) are from Algeria, then a French Colony. He is still a soldier, he has signed on again, because, as he wrote, he doesn’t know what he would do in normal life, after what he has been through.”

What sort of everyday materials, toys and props are used to create and animate the horrors of the miniature world in The Great War? Kalker: “In The Great War, the landscape is the main character, as well as a metaphor for the people who are hidden in it in their trenches. In the beginning of the show, the landscape is fresh and green, and slowly it gets wounded and becomes a rotting mixture of mud, corpses, barbed wire and broken weaponry.” Helle: “We create this evolving landscape on stage, on a large table covered with potting soil – a lot of it. The props are a mixture of everyday materials, such as parsley for trees, powder sugar for snow (which melts beautifully as it starts raining out of a plant sprayer) and things that we made ourselves, like cardboard stairs going down to a dugout, a city under fire made of photocopies of postcards from that region and era, a World War II toy tank modified into a box-like tank from World War I. With the legs cut off from an Action Man figure, we stumble through the mud. Filmed up close. they look astonishingly real. You don’t need very sophisticated miniatures to create realism. Crudely made props and scenery can be very suggestive, precisely because they leave much to the imagination.”

How do you achieve such realistic-looking explosions, fire and smoke? Helle: “The fire is made with penetrating oil, sprayed and ignited. The flames aren’t that big, but filmed and projected on a big screen they look huge and intimidating. The explosions are made by blowing with a pressured air gun into the potting soil, so that earth flies all around. Combined with the loud sound effects. they look very realistic. For poison gas, we use dry ice; CO2 frozen solid. When we add boiling water, it produces a very heavy mist that creeps over the earth and the dead soldier puppets.”

Can you describe how some of the sound effects are created, and also how they add to the potency of the production? Arthur Sauer: “The sound gives a sense of continuity of location (you can hear things that are not visible in the image or fall outside the frame of the camera) and adds to the realism. For example, someone is running in no-man’s land during an attack during which there is a lot of bombing and shooting, the camera cuts to the inside of a house, but you still hear the sounds of this bombardment: you ‘know’ you are still in the same place, although you can’t see it. I decided to use both ‘real’ and ‘imaginary’ sounds. A machine gun is played on a tin, with marbles inside, by rattlng with two xylophone sticks on top. In another part a machine gun is played by a sample of a recording of a real machine gun, which is sculpted in such a way that it shakes the audience. We also use the tin can to give an impression of the sound of a tank – by rambling a half coconut on top of the tine and pressing a running vibrator against it, backed up with a low droning electronic sound.”

What do you consider to be the most powerful moments or scenes in the production? Kalker: “There a several powerful moments – a gas attack is one of them, and the scene in which the audience gets to look through the eyes of a soldier who is in the middle of a heavy attack. Sauer: “To describe them all would be a spoiler, but what we can say is that the whole audience will be silent and impressed during the last scenes of the show…”

29-1-2018