An ingenious, troubling performance

This “live animation” show brings the claustrophobia, inhumanity and visceral muck of World War I to grotesque life using everyday items and miniatures: you’ll never be more affected by a dismembered plastic figurine.

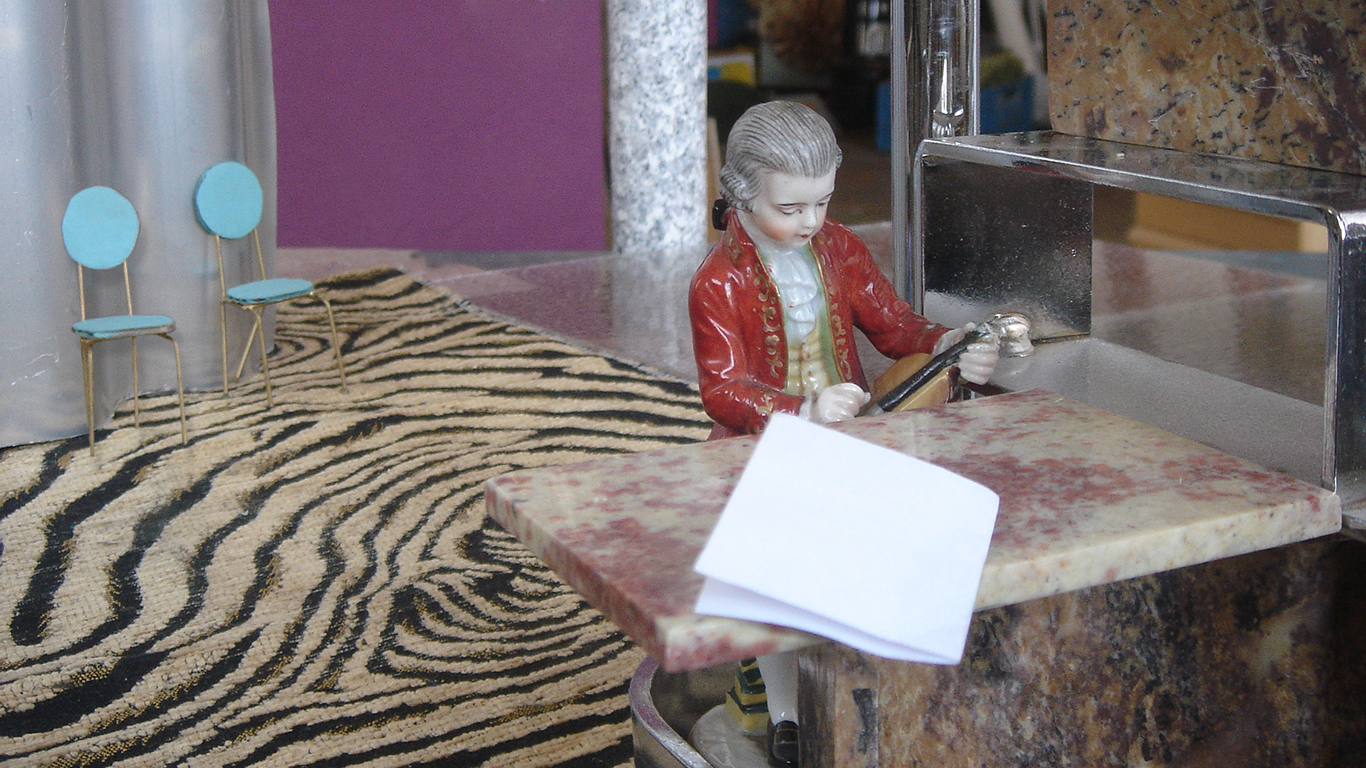

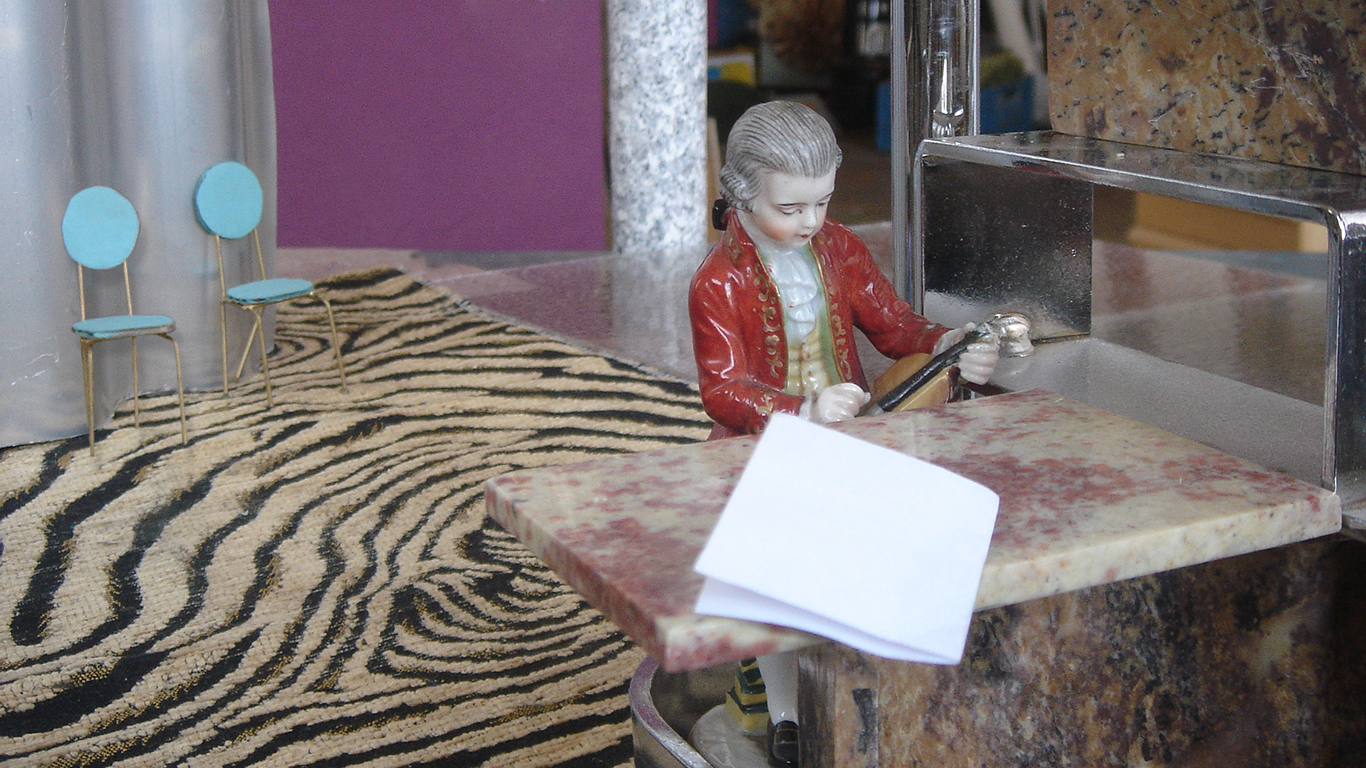

Dutch company Hotel Modern returns to the Adelaide Festival, five years after its show Kamp moved local audiences with its miniature representation of life in a Nazi death camp. The set-up for The Great War is similar. On one side of the stage, Arthur Sauer controls an array of music and sounds – the clatter of machine-gun fire, the roar of artillery – and more subtle, but equally affecting, noises – the squelch of boots in the horrific soup of mud, rotting bodies and detritus. Elsewhere on stage, puppeteers Herman Helle, Pauline Kalker and Arlène Hoornweg manipulate miniature figures, mostly on a huge table covered in potting mix, but also in an aquarium which serves as a murky simulacrum of the English Channel. Cameras project the action onto a screen at the rear, so the audiences’ eyes can move from the “animation” to the performers themselves manipulating the scene and the cameras. The performance concept – if not the subject matter – may seem like intriguing fun but as the one-hour show progresses, the form becomes linked to the themes in a way which is, ultimately, very moving.

The show begins with a documentary-style description of the complex origins of World War I, with a top-down camera filming a vintage map of Europe. Various symbols are placed, with increasing freneticism as the situation deteriorates, on the map as Franz Ferdinand is assassinated, Germany invades Belgium, and country after country declares war. The narration rises to fever pitch, the words blurring as the history lesson devolves into chaos.

The performers move to the larger tables where the butchery takes place. Green fields and forests (represented by stalks of parsley, broom-heads and the like) are destroyed by gas-torches; clopping horse and carriage are replaced by metal tanks and tiny rolls of razor wire. From here, the narration is all (real) first-person accounts of the front. Elation at cutting down an enemy column is replaced by a litany of increasing despair: tank crews burning alive, a soldier with his leg blown off screaming in no-man’s land for hours, children and women drowning after a torpedo attack during an attempted Channel crossing.

As you might imagine, this requires intricate choreography by the performers who, at times, consciously allow their hands to come into camera shot: reshaping the landscape, moving vehicles and animals, placing tiny pieces of scenery. However, as the performance increases in tempo, we are brought into claustrophobic acquaintance with the fine detail of the trenches and soldiers under fire. The performers stage strategic retreats from view. With virtuosity, a single performer – at times – holds a camera in one hand, while recreating sprays of machine-gun fire with the other; we see through the eyes of individual soldiers, even, at one point, a nerve-wracking descent down the steps of a captured German bunker, rats scampering on the ground, an abandoned table set with a bottle of wine, corpses slumped on the floor. One of the most realistic and gripping pieces of puppetry involves a tight camera shot of the legs and boots of a soldier – squelching gingerly through the trenches. With our imaginations activated, the potting mix-landscape is filled with unseen horrors.

At the end, the performers invite the audience to come up to the stage, to see the props up close and ask questions. The audience – drawn from a very wide range of ages – were able to see the spent gas cartridges, inspect the tiny sets, and wonder at how everyday items can be transformed into such a haunting landscape. As with the appearance of the puppeteers’ hands in the shot, this proximity of the ordinary and the human with the brutalities of battle is actually part of The Great War’s power: the butchery of the war was wrought with relentless intentionality by human hands; the fields of France were churned with the blood of real men who once led ordinary lives filled with ordinary things.

It’s an ingenious, troubling performance.

9-3-2018