Dutch greed in Indonesia (interview)

In Our Empire, Hotel Modern theatre group show how the Dutch established their trading empire in the Indonesian Archipelago. This is a vivid and imaginative retelling of a history steeped in violence and duplicity.

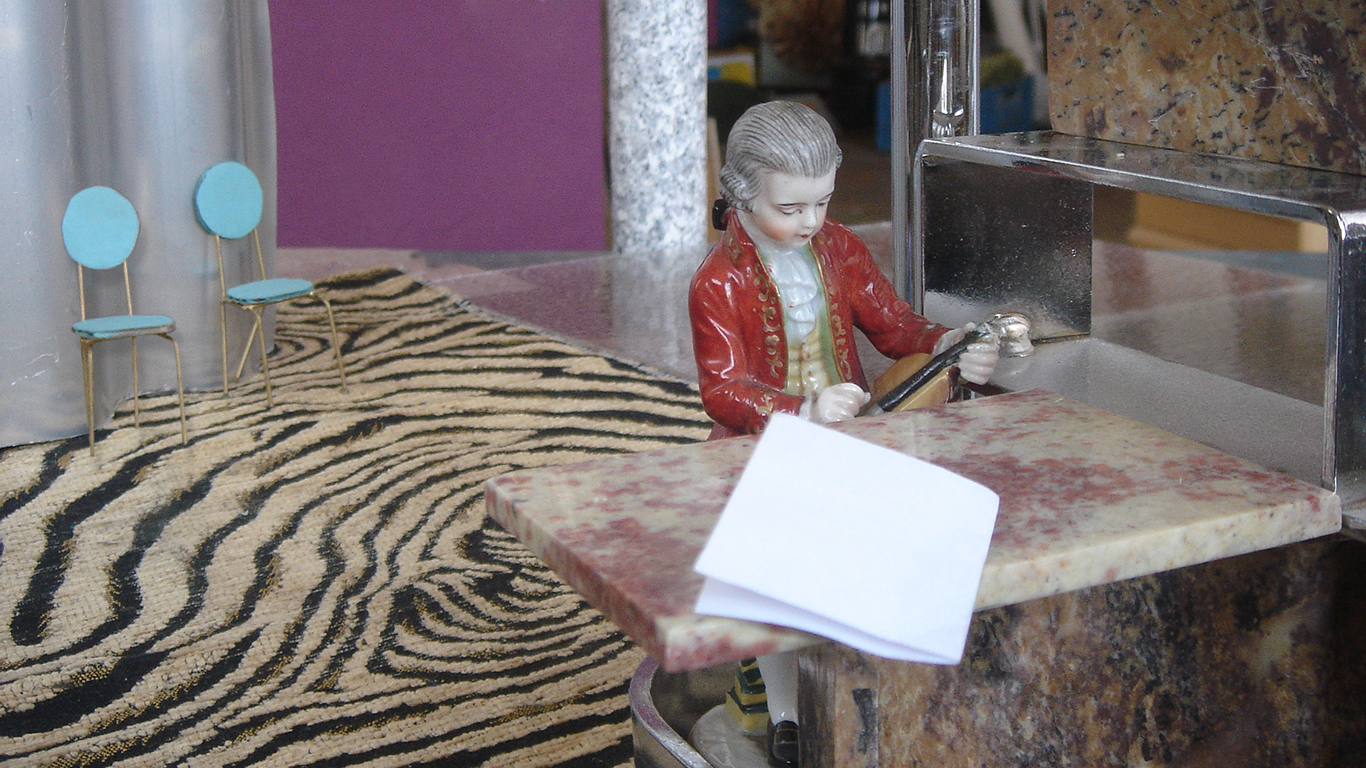

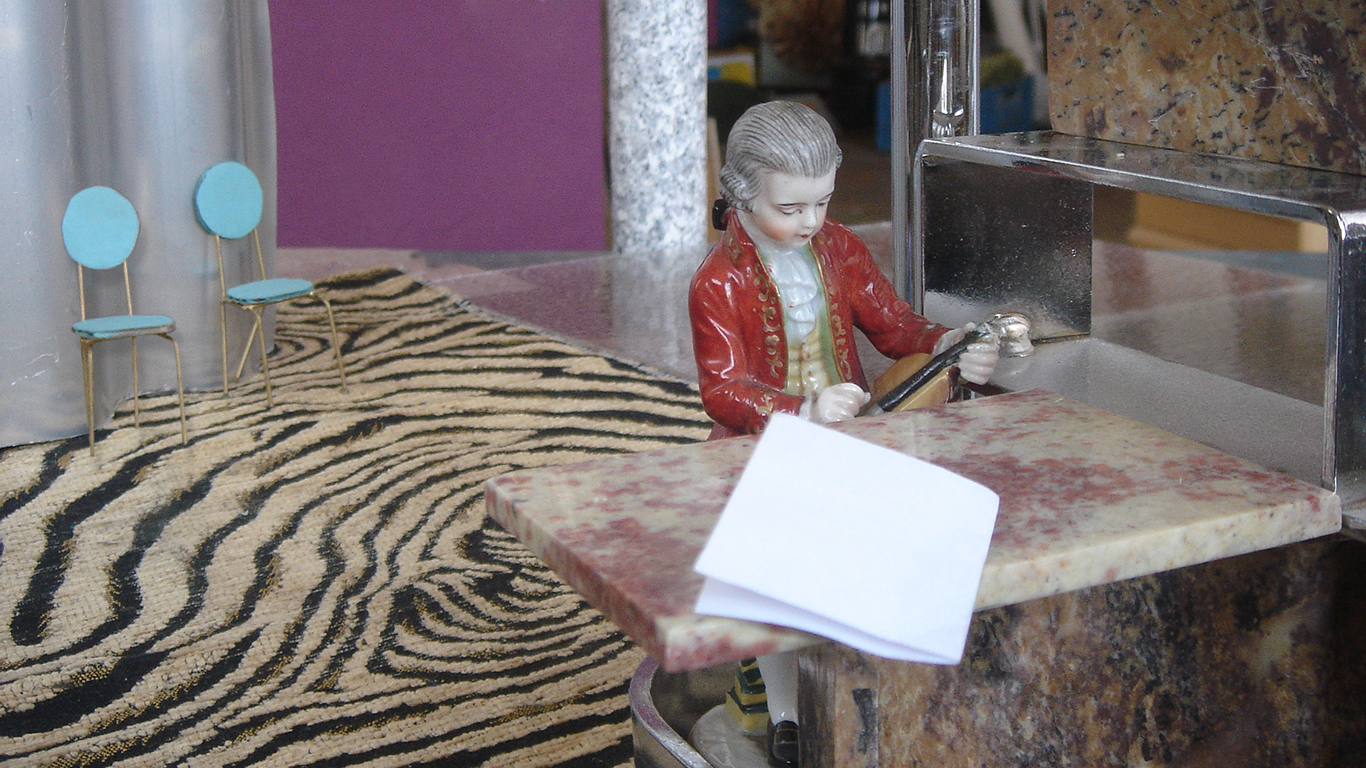

In the chaos of a gun battle the shots ring out in deafening, deadly salvos. Clouds of smoke from the guns obscure our view of the action, but when they briefly lift we see that the firearms have clearly been effective. The bloodied victims lie to the left and to the right: men, and women and children, too. The men are armed with at most spears and clubs that are no match for their attackers. This scene comes not from action film, but from the latest play by Rotterdam theatre company Hotel Modern, titled Our Empire. It is the first part of a planned trilogy on the role of Dutch colonisers in Indonesia – the Dutch are the figures with the heads of sheep. Sea battles, ambushes, spice harvests, negotiations and duplicity, deceit and intrigue, the wealth of kingdoms, and Dutch greed: all have their part to play in Our Empire. Hotel Modern has been known since 2001 for its use of detailed scale models to tell its stories, filming them and projecting the resulting footage onto a large screen in plays that have followed the fortunes of a French soldier in the First World War, and life in a Nazi concentration camp.

This first part of Our Empire spans from the early 17th century to 1670, the period in which the Dutch East Indies Company (or VOC for short) built up its trade monopoly in the Indonesian Archipelago. It is a past with which artist Herman Helle, a member of Hotel Modern, feels a personal connection. ‘My parents were born in Indonesia,’ he explains, ‘All four of my grandparents went there from the Netherlands. So although I grew up on the Dutch polder, our lives at home were suffused with a sense of the good old days in Indonesia, the tempo doeloe. My parents wanted us to have a childhood as wonderful as their own: we walked barefoot; we ate Indonesian food; people coming from Indonesia were welcome visitors. For all I knew we were Indonesian. My parents were no invaders, and as far as I was concerned they had every right to their wonderful youth. But that happy narrative does clash with the historical reality, which has got a lot of dark aspects. And that’s what makes it very interesting, too. But what do you do with a legacy like that, for god’s sake?”

There’s often a personal component to Hotel Modern’s plays. Kamp, for example, is based on the experiences of members of Pauline Kalker’s family in concentration camps, and in God’s Beard Arlène Hoornweg dealt with her own mother’s death. Herman Helle had been wondering for a long time whether he should use his own family history for a play. ‘I know all about tempo doeloe, but that story’s been told a hundred times already,’ he says, ‘You could maybe do something about the war of independence, but it’s more interesting to look at what underlay it. To do that you need to go right back to the beginning. We decided to start at the point in the early 17th century when the Dutch captured the island of Ambon from the Portuguese. We end in the Dutch colonial capital Batavia [now Jakarta] in 1670, by which time the VOC has secured a monopoly on the spice trade. That’s the story we wanted to tell – from the perspective of Indonesians.’

To get an idea of

what took place and the living conditions of the various population groups in

this period, the group consulted historical sources and talked to historians.

It didn’t make working any easier. ‘What drives you mad is there’s so much you

don’t know. Engravings of villages on Ambon show very Dutch-influenced homes.

Banda was once the only place where nutmeg was harvested, and Jan Pieterszoon

Coen wiped out the entire culture there, and for a long time the global trade

in the spice was based on these islands. So they must have been richly dressed.

The scale model villages we built for the play are based on other Moluccan islands.

And for a scene at the Javan court of Mataram, too, we wondered what it must

have looked like, what kind of clothes people wore. You come up with all sorts

of ideas, but you won’t find confirmation anywhere that that’s what it was like

in reality.”

Hotel Modern spent a year building the scale models for Our Empire, and similar care went into Arthur Sauer’s composition of the music and sounds that accompany the scenes and add atmosphere. ‘No one’s got any idea about the music of the time or what a busy market sounded like,’ explains Sauer. ‘And you can’t just go to one and make recordings – there’s always a moped around, making a racket. The group chose to take a kind of documentary approach. I added in a layer of atmospheric sounds, with an emphasis on higher sounds when good things happen, and lower sounds to represent evil. Apart from that, I collected as many recordings as I could find of the insects and birds belonging to the islands where the play is set. The most successful sound, I think, is when a Portuguese ship sinks during a sea battle. It wasn’t possible to portray it visually. I used the sounds of snapping bamboo canes for that – lots of short cracks that I built up, stretching some of them, in loads of layers. It took me ten days to make.”

2 January 2020