Holocaust on stage

Recreating —if that is the right word— the daily routine of mass murder at Auschwitz with miniature puppets made of plasticine may not seem a promising enterprise. However artfully done, it could make what actually happened look trivial, like a kind of game.

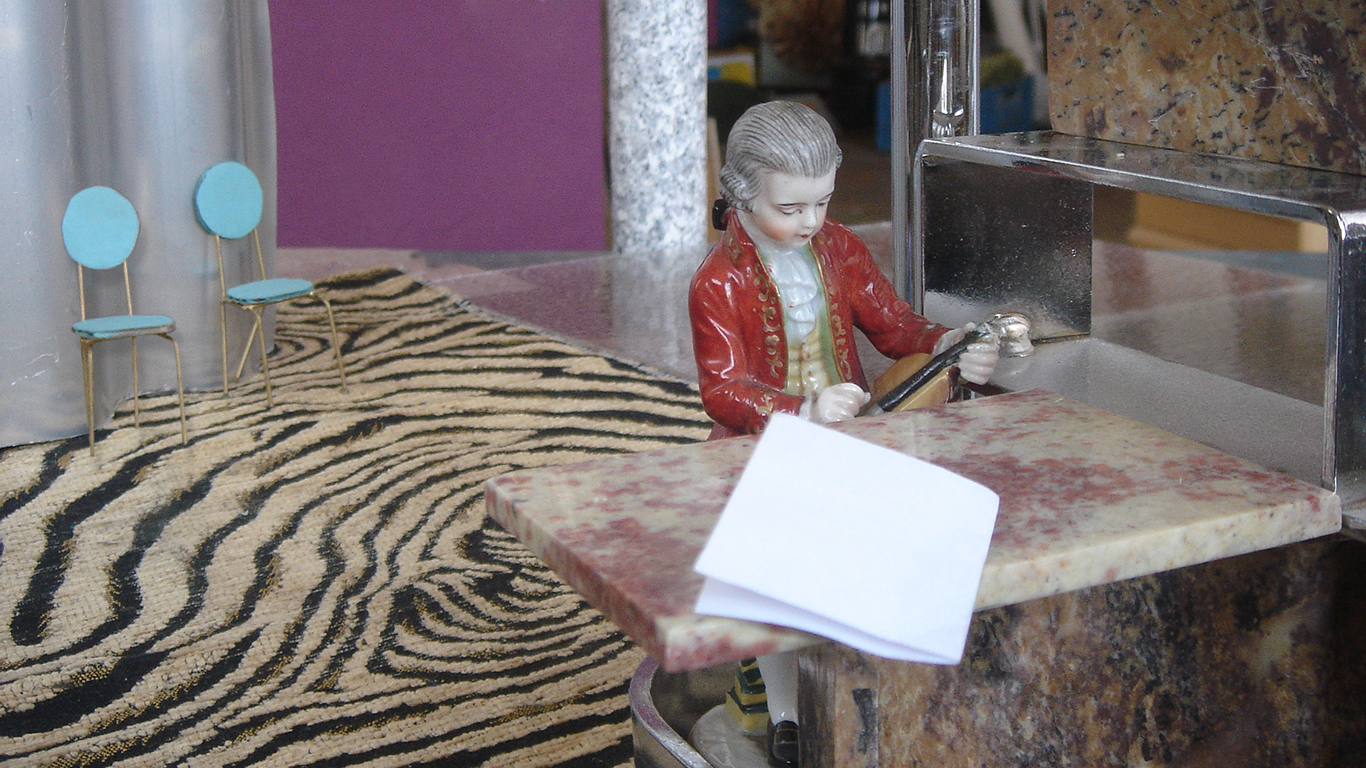

And yet Kamp, staged at St. Ann’s Warehouse in Brooklyn in the first week of June, by a Dutch group called Hotel Modern, was weirdly gripping. The camp was presented as a room-sized model made of paper and cardboard. All the notorious landmarks were there: the Arbeit Macht Frei gate to Auschwitz itself, the barracks of Birkenau, the extermination camp nearby, the gas chambers, the watchtowers, the SS casino (where the Germans relaxed after a hard day’s work), the railway ramp, the appelplatz, where prisoners were made to stand for hours and hours, in dusty heat and icy cold.

While one or two members of the theater group, comprising of Pauline Kalker, Arlène Hoornweg, and Herman Helle, would manipulate the bald, pale, emaciated puppets—falling out of the trains, slurping the last drops of their watery soup, being worked to death, beaten to death, shoved into the gas chamber, cleaning out the gas chamber—another filmed this daily camp routine, as though he were a news cameraman, permanently on hand to record what was happening and project it onto a screen. The finger-sized puppets have individual faces, like the 200 BC Chinese terracotta army in Xi’an, most of them frozen in expressions of terror reminiscent of an Edvard Munch painting. The SS men and guards, on the other hand, are expressionless cutouts from old photographs. In an odd way, they look more dead than their victims.

There is no dialogue in the piece, which is as much an art installation as a theater play, just sound effects, of the trains coming and going, of people aimlessly shoveling the earth, of steel doors clanking shut, of Zyklon B being funnelled into the gas chamber, of drunken SS men singing marching songs in the casino, of a truncheon beating a sick, exhausted slave worker over and over, until there is nothing left of him but a few broken sticks wrapped in a rag.

It works, I think, precisely because of the artificiality, the stylization of the performance. The details evoke reality, often to horrifying effect, without trying to mimic it. Puppets can seem more real than actors, because they leave more to our imagination. Stripped of his striped camp garb, the naked puppet becomes transparent, as he is pushed into the gas chamber with the others, looking terrifyingly vulnerable. No dialogue or action is needed to illustrate the atrocity of the scene. Actors can never reenact what happened in a place like Auschwitz, at least not realistically, because what happened cannot be recreated. The more we aim for a realistic portrayal of such extreme violence, the more likely we are to produce a form of kitsch.

Steven Spielberg’s film, Schindler’s List, demonstrates this. The terror seems most real when violence is not actually shown—for example, in the scene at the station, where sealed cattle trains stand idle for hours in the baking sun, while the people stuffed inside are dying of thirst. Remember the crass, beery laughter of the German officers when Schindler attempts to relieve the prisoners’ thirst by hosing water into the trains. This is effective. The cruelty is palpable and shocking, whereas the scene inside the gas chamber is not. Spielberg knew that he could not show an actual gassing; how could you possibly act that out? But when the gas chamber turns out to be a shower room, it feels both like a cop-out and, as it were, a scene too far.

The harder we try to show what cannot be shown, the more elusive reality often becomes. Some things must be left to our imagination, not because it allows us to share the experience of real victims, for that, thankfully, we cannot do, but because a poem, or an oblique image, a faded photograph, a discarded suitcase, a child’s broken toy, or a plasticine puppet, can jolt our emotions by suggestion, which somehow is more effective than attempts at direct portrayal.

Much has been written and said about Adorno’s famous declaration that “to write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric.” I don’t think he meant that no poems should ever be written after the killing. A more likely interpretation of his dictum is that barbarism, of which Auschwitz was the purest example, cannot be the stuff of poetry. There is no poetic meaning to be culled from exterminating millions of people. In fact, there is no meaning in it at all. To call the victims of Nazi mass murder “martyrs,” as is common in the language of Holocaust remembrance in Israel and elsewhere, is to give their deaths a higher meaning. They did not die for their beliefs, after all, or for a cause. (Being born Jewish is neither a belief nor a cause.) Part of the horror of what happened is that innocent people were killed for no reason at all. Auschwitz was a murder factory. Killing was a routine.

Martyrdom also implies that people have a choice in the matter. Christian martyrs, or indeed Muslim suicide bombers, are called martyrs by their communities because they were willing to die for their beliefs. But the fact that victims in the Holocaust had no choice does not mean that they were no longer human. The best accounts of the death camps, in fiction and non-fiction, by authors such as Primo Levi and Imre Kertesz, show that even under the most extreme circumstances human agency is never entirely extinguished. Primo Levi hinted at that, albeit darkly, when he insisted that the best people rarely survived. Survival was a matter of luck, but also of knowing how and when to take care of yourself—and only yourself. When Kertesz, author of Fateless, returned to his native Budapest from Auschwitz and Buchenwald, well-meaning people commiserated by saying he must have gone through hell. It was not hell, he would reply, but a camp made and inhabited by people. And he was not just a passive victim, or some abstract denizen of an imaginary place, but an adolescent, who happened to grow up in Buchenwald. He did not mean to diminish the dreadfulness of that experience, but he wanted people to see that it was still an experience that he lived through. Kertesz insisted on his autonomy, such as it was, precisely because his tormentors had tried everything to take it away from him.

This is why the most successful accounts of the Holocaust have been witness accounts. They restore individuality, they give the victims faces and voices. The alternative is to use suggestion. Poetry—pace Adorno—is ideally suited to this. And so is the kind of performance put on at St. Ann’s Warehouse, where the beating to death of a plasticine figure evoked precisely the barbarism that Adorno thought was beyond the bounds of art.

16-06-2010