Hotel Modern uses the theme of mortality to connect the everyday and the magical

It’s all comings-and-goings (and waitings) in Snail Trails. This performance by Hotel Modern could also be described as the story of a woman descending into senility, but that would not do full justice to the work of this Rotterdam-based collective, producing since 1996. Snail Trails is a philosophical statement about life and death that is related to the work of absurdist writers such as Ionesco and Beckett and takes its lead from the Surrealists. In the performance, the fundamentals of human existence, time and space, lose definition and completely disperse into this magical world. At the close of the performance there even appears on stage, as a modern deus ex machina, a unicorn….

The materiality on display is affecting, even more so because not a word is spoken. On stage, the room and its inhabitant seem old-fashioned, old and shabby; the props are bizarre but real and the atmosphere is gloomy. The old woman in the green dress is not really old, although she moves with difficulty, shuffling; the ugly brown walls of the abode are cardboard. A large hat and a faded jacket hang on the hat stand; boots stand at its foot; a photo of a rhinoceros adorns the wall. Below this stands a plant in the shadow of light emanating from a projector on the floor. To the left, under the head of a giant pig, the woman sits, performing her daily rituals in the strange world of her fantasies, nightmares and memories. But first of all, light probes the darkness: an utterly commonplace wall lamp moves all about with her arm. Together with her, we look around.

A cup is pushed on to the table through the wall by the hand of an unseen person, another sets the coffee pot down. Someone, concealed by hat, jacket and boots, walks away. The woman pulls a large prawn from the biscuit tin and ponders it with curiosity and slight surprise. Ponderously, she gets her legs moving and reaches the other side of the room, touches a cross on the wall there and carries a banana across the space, like a candle, in her outstretched arms. The somewhat unpleasant atmosphere is moderated by harpsichord music when the woman put a record on. The visual dramaturgy is inspired by the fantastical world of fairytales. The central motif is an in-and-out movement, but the woman’s nightmares, the rather forced materializations of Freudian symbols that torment her, are also key.

In this first part of the performance, the experience – for both the woman and the observer – is not particularly intense and what is on display is neither shocking nor by any means new. The actress portraying the woman successfully evokes the stiffness of limbs and a repetition of movement that seems to be driven not by the mind, but only by habit. She is nonetheless not sufficiently mechanical to become a ‘panoptical figurine’ his life is reduced to a number of functions, because she is stuck in a naturalistic, imitative reproach. With hindsight, this was perhaps the intention, because the meaning and metaphorical value of this first section only become evident in combination with the second part, a film in which the woman takes on the form of an entirely objectified human, a puppet, a marionette.

The transition into another form of existence is marked by a kind of visual and aural dance macabre. Half of the plant disappears, the clock on the wall speeds up and stops, the telephone rings but there is no one at the other end of the line, the table falls and thick syrup runs over the tabletop, the walls become elastic and slide apart. The woman disappears behind a red curtain and on stage a huge prawn cuts through a rope allowing the projection screen to descend.

This great rupture between the material, dimensional world of the objects and the body, on the one hand, and the magical world of the animation film, on the other is absolute and results in a radically altered perception. One form replaces the other but they are connected by the movement in and out; going by coming.

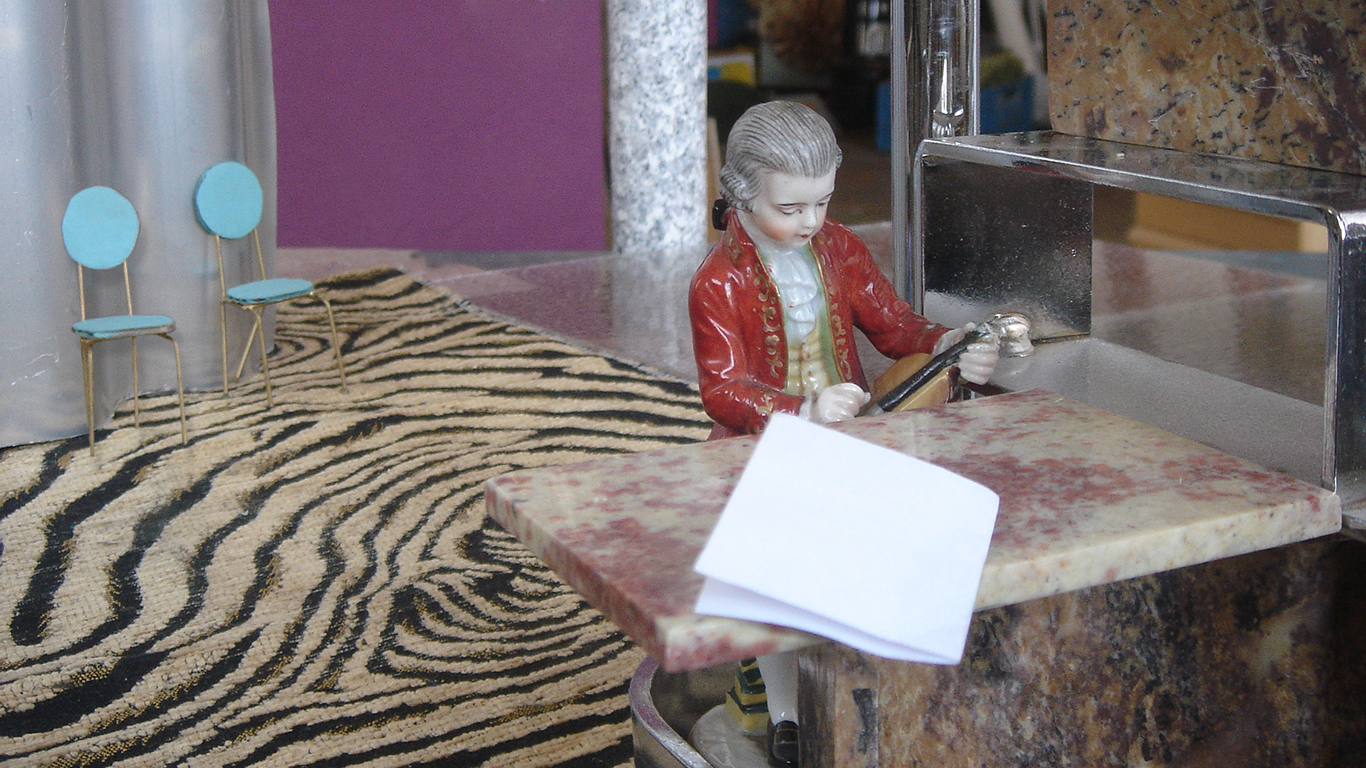

In this fantasy world created by an artist, the woman, now a puppet, visits various spaces: a department store, a fun fair, a restaurant. These are all places belonging to nobody and everybody, where events and potentiality run parallel; past and present coalesce, but equally the here and now is very much at hand. She wanders this urban landscape of colorful lights, transparent as a lollipop, and eventually finds a place on the bench opposite the bus stop.

On the escalator in a department store she ascends together with the prawns, at a funfair she sees an enormous octopus revolve, irons race by at deafening volume, prawns step in and out of a bus and the heavens take on the red hue of evening, day becomes night, then morning glow returns.

Hitchcock’s archetypal messenger also plays a role in this fascinating and magical world of film: as if the crow’s gaze represents the camera, together with him we follow the feet and the footsteps of the woman. And then with dizzying speed, the lift passes hundreds of floors to the roof, surrounded by mist-bound nothingness. Is the woman flying through space, unhampered by gravity, or is she giving sweets to the giant rhinoceros from whose mouth a hand projects? This poetic and absurdly humorous metaphor for death is comforting.

Hotel Modern’s approach, combining stagecraft, film, visual arts and music, is successful. It is also amusing when they poeticize the absolute banality of everyday reality, disrupting established significations. Their prizewinning performance The Great War was also selected for The Theatre Festival. Their work recalls mixed media performances dating back several decades, but using their aesthetic pluralism the makers endeavor not to blend the various forms but rather to juxtapose them. In Snail Trails the meaning does not emerge through merging, but rather through the absolute aesthetic diversity; the theme of mortality viewed from the perspective of timeless time connects the material and the immaterial, the everyday and the magical…

2002