Small figures reveal big Holocaust story. Kamp recreates Auschwitz in miniature (interview)

When the Nazis invaded Holland in May of 1940, Pauline Kalker’s grandfather, Joseph Emanuel, who was Jewish, went into hiding. He moved from house to house, evading the Nazis for several months. But soon he was caught. The Nazis tortured him for three days, hoping to get information about where other Jews were hiding, but he did not crack. “They broke his nose and some ribs, but he didn’t say anything,” Kalker said recently. The Nazis allowed him to recover in a hospital, though soon after he was healthy he was transported to Auschwitz. He died a month later, on Oct. 1, 1943.

Kalker never met her grandfather, but said in a phone interview, “I was curious about who my grandfather was. I wanted to be with him.” To that end, she and her theater company, Hotel Modern, based in Holland, created the miniature theater show Kamp, which opens at St. Ann’s Warehouse, New York, this Wednesday night.

The show features a model of Auschwitz, complete with 3,500 finger-length inmates, and depicts the camp’s routine, gruesome events — beatings, gassings, cremations and starvations. The Holocaust is “so big,” said Kalker, “that you can’t tell the whole thing. But we felt that in miniature theater you could tell it on a much bigger scale.”

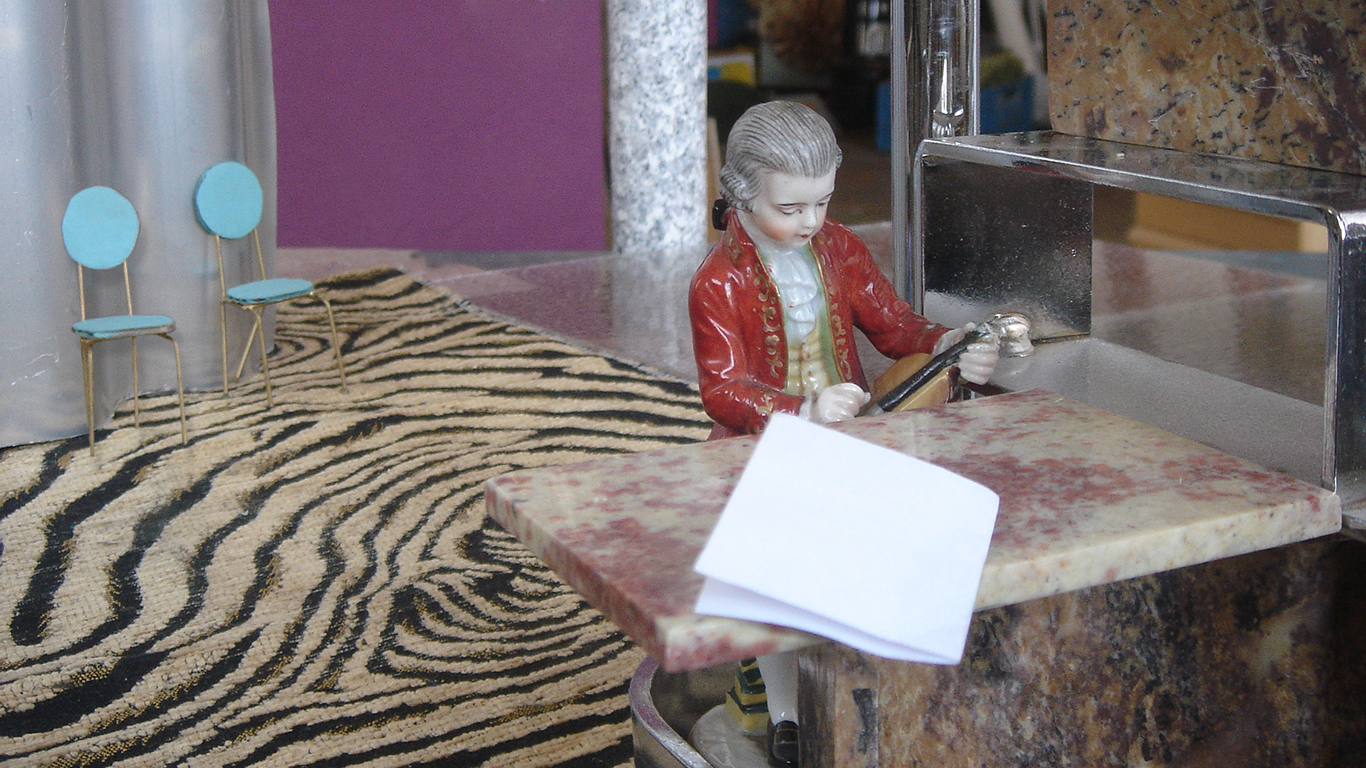

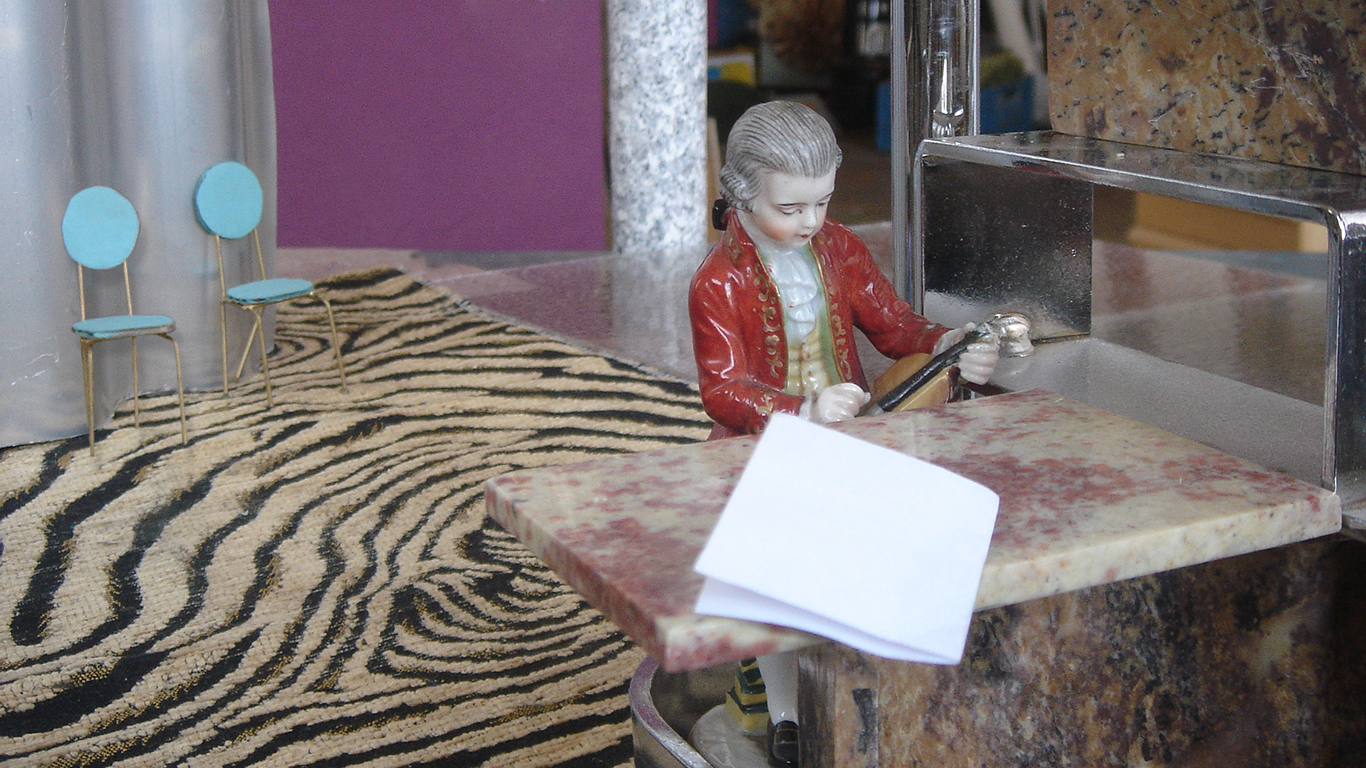

For the show, originally created in 2005, Herman Helle, the visual artist in the company, hired 10 local Dutch artists to build a near-exact model of Auschwitz. Helle undertook an intense research campaign, which included a visit to the camp, a viewing of several documentaries, and the study of camp blueprints, including its gas showers and ovens.

“Sometimes it was strange,” said Helle. “At a certain point, I was looking at the gas chambers [the Nazis built] and thought to myself, ‘That’s not the smartest way to build it.’ Then I caught myself, and said, ‘My God, I’m improving the gas chambers in a way.’”

During the show, which lasts just under an hour and plays through Sunday, several company actors film the action live. The footage is projected on a giant screen behind center stage, where the audience can see the actors moving the tiny figurines and filming. Though there is no dialogue and no real plot, the intricate documentation of how Auschwitz functioned, Kalker said, is drama enough. “We wanted to show the machine working,” she said. “That’s the dramatic thing — that it existed. People did this.”

But does the sweeping diorama come at too steep a price? Are the victims again made anonymous? When asked this, Helle said he did not think so. The company debated whether to focus on a few characters with a more traditional storyline, but decided against it. The nature of toy theater, he said, seemed to make any specific characters appear contrived — too cute, even. “It wasn’t sincere,” he said. “You see a character being beaten to death by a bodyguard, and that’s as close to an individual character as you get.” Still, the individuality of the inmates was not lost: “You zoom onto the faces and you realize that it’s about human beings,” he added.

Since all 3,500 figures are created by hand — their bodies made from simple wire covered in striped fabric, their heads from hand-rolled bits of clay — each one appears unique when projected on screen. You notice that each face, even in its abstract form — two poked holes for eyes, a sliced line for the mouth — is actually quite different. “People find it very real,” Helle said.

Contemporary toy theater often plays in the surreal mode (you could imagine Tim Burton having a field day with it), so the realism of Kamp was strangely refreshing, said Susan Feldman, the artistic director of St. Ann’s Warehouse. “I’ve been there, to Auschwitz and Birkenau,” Feldman said, adding how life-like Hotel Modern’s production seemed. “In Kamp, you see the daily life of what happened there, whereas a lot of the time [in theater based on Auschwitz] that’s just background.”

St. Ann’s Warehouse has a long history of staging both miniature (or “toy”) theater, as well as puppetry. “It’s been part of [St. Ann’s] DNA since the beginning,” Feldman said. (While toy theater and puppet theater are different, both, in essence, use props as characters, and theater directors often bundle them on the same bill.) In 1980, the year the venue opened, Feldman invited the renowned puppet company Bread and Puppet to stage a work. Since then, as toy and puppet theater has become increasingly prominent (think “Avenue Q” and Basil Twist), she’s added new companies to her roster almost every year.

Kamp is in fact one of several miniature theater performances being staged in this year’s ninth annual International Toy Theater Festival, which runs at St. Ann’s through June 13. But Kalker said that she herself avoids the name “toy”. To her, it diminishes the seriousness of her work. “We never use that word,” she said. “We find that the power of using models is that you can do really big themes.”

Kamp is not Hotel Modern’s only miniature work either. The company, founded by Kalker and Arlene Hoornweg, both actresses, in 1997, made its first miniature show in 1999. After creating several avant-garde plays, the addition of Helle to the company inspired them to try something even more radical. Helle had a side career making models for prominent architects, including Rem Koolhaas, and proposed a show based on the workings of a modern-day city. City Now was the result, and since then, they’ve made four other miniature-style shows, including Kamp.

The novelty and intricacy of their miniature work has made Hotel Modern wildly popular. But Kamp was the first show to deal with such a charged subject, and occasionally audiences have not been pleased. Helle recalled a performance in Germany not long ago, in which a Q&A was held with the directors after the show. “One person got up and said angrily, ‘It’s a banalization of the Holocaust. It’s kitsch.’”

But Helle said that most of the audience seemed to disagree, finding the show deeply compelling. He reasons now that the intense negative reaction — which he’s only experienced in Germany — probably had a lot to do with that fact. “It’s still a very difficult subject to discuss there,” he said.

There have been other memorable reactions, too. Kalker remembered the first time her own father and aunt saw Kamp, in 2005. As children, both also went into hiding when the Nazis invaded Holland, but were separated from each other and their father, Joseph Emanuel, during the war years. Neither went to a concentration camp, only finding out about their father’s death after the war was over.

Kalker recalled seeing tears come down her father and aunt’s faces as the show came to a close. “My father and his sister,” Kalker said, “had never really grieved together after their father died. They did not talk about it when they grew up, and they could never give him a proper funeral either.” For them, she thought, this must have been something quite like one.

01-06-2010