- Premiere Year 2022

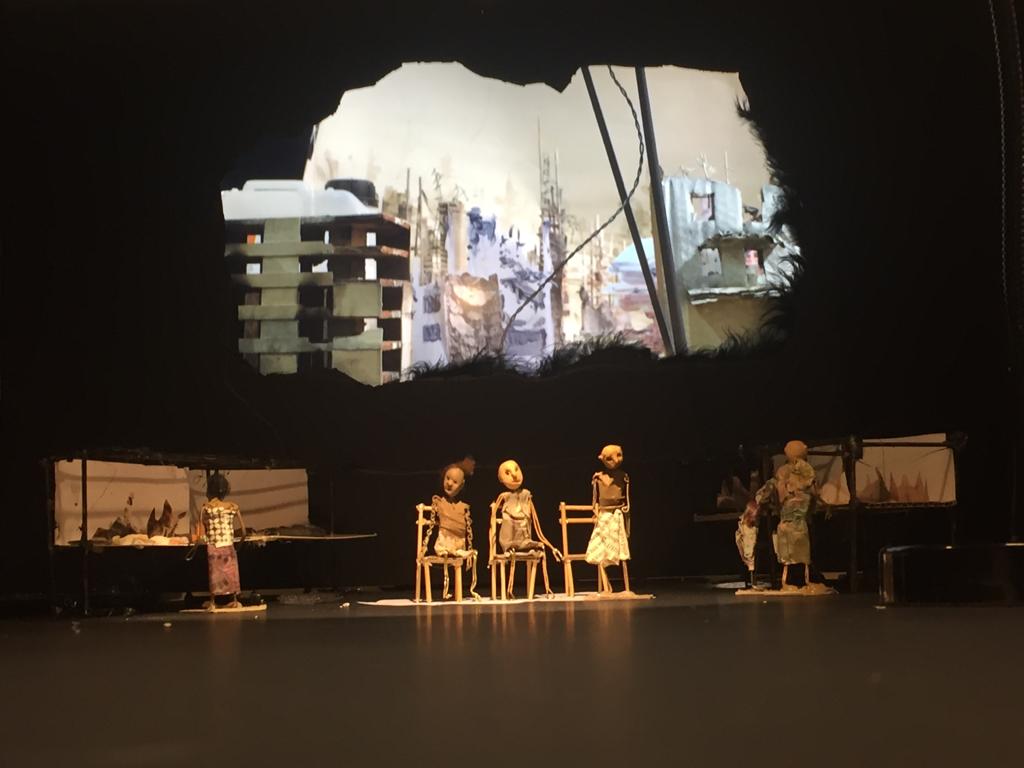

Staatsoper Stuttgart, one of the leading German opera houses, invited three renowned artistic teams to stage the three acts of Richard Wagner's The Valkyrie. Hotel Modern was asked to design the first act. Herman Helle, Pauline Kalker and Arlène Hoornweg situate their part of this mythical love drama in the apocalyptic world of a civilization that has perished: an endlessly devastated landscape, in which rats seem to be the only living creatures.

The three soloists perform their roles surrounded by the live animation film set and the actors/puppeteers of Hotel Modern. Musical director Cornelius Meister conducts the Staatsorchester Stuttgart.

In the second act, light artist Urs Schönebaum will make underlying structures visible, whilst installation artist Ulla von Brandenburg will transform the third act into a colourful choreography. With a ticket for The Valkyrie the audience gets to see and hear three adventurous acts in one performance.

"In the first act, the concept leads to a unique, dense and stirring unity of (cinematic) images, acting singers and Wagner's powerful music." (IOCO)

"On both sides of the stage there are long tables with the many small models needed for the live film. Humans will not appear on film, only rats that are on the run. The world around them is devastated, it is the end of a war, the houses are only skeletons, wrecked tanks stand in an apocalyptic landscape, the rats are looking for protection that doesn't exist. Today one might read this like a commentary on world events, but it was all already written by Wagner. Hunding and Siegmund come from a clan war, Sieglinde has experienced violence in the past. Three injured people meet here, while on screen a bit of rosemary timidly greens, a blissful moon rises and northern lights scurry across an icy surface." (Süddeutsche Zeitung)

"The images of the spring night are of great beauty („wachsende Helligkeit des Mondscheines“): a snowy winter landscape, in which the first green spriggs appear." (Klassikkritiker)

"The three soloists hardly act, some facial expressions, a few statuesque gestures, is all. But what could otherwise be seen as a failure in stage directing becomes a fascinating trialogue between the filmed images, the characters and the music." (Süddeutsche Zeitung)

-

Reviews & articles

-

Three teams of directors stage Richard Wagner’s “Valkyrie” at the Stuttgart State Opera. With amazing results.

At the end of the whole "Valkyrie" it's no longer about gods and worlds, but about people, real people. That's amazing, and it rounds off an experiment that, in all its disparity, works out fascinatingly well. Also: when do you ever get to see three opera productions in one evening?

by Egbert Tholl, Süddeutsche Zeitung Read the whole review

The small rat is very excited. She whizzes along a train track, past ruins, through destroyed houses, past tubes of paint and the remains of other things needed to create art. The rat is looking for shelter, a few of its own kind are chasing it, it moves exactly to the rhythm of the music, driven by the roaring overture. You see the rats large on a screen, that looks like a hole in a wall or, depending on the lighting, like the crown of the ash tree, whose trunk stands here quite lost on center stage. But you can also see them in real life, puppets on threads moved by people, scurrying across the stage.

The Stuttgart State Opera is once again using an idea that caused a sensation more than 20 years ago. At the time, artistic director Klaus Zehelein commissioned four different artistic teams to stage the four parts of Richard Wagner’s “Ring of the Nibelung”. His successor Viktor Schoner is now repeating the process and intensifying it. Not only is each part of the “Ring” created by a different director, in “Valkyrie” there is a different artistic team for each of the three acts. The opera starts with the first act of Dutch theater company Hotel Modern, which consists of Pauline Kalker, Arlène Hoornweg and Herman Helle, and what they create is quite sensational. As is this whole “Valkyrie”: the contradiction of the directors’ concepts seen here is an exciting undertaking.

Hotel Modern were guests at the Salzburg Festival in 2007, where they presented their deeply moving theatre production “Kamp”. They recreated a day in the Auschwitz concentration camp, without text, just with many small figures who died, suffered, went to the gas chambers in a model of the death camp. The audience saw a film that referred to the canon of images of horror and at the same time they saw how it was made: the stage model and the figurines in it were filmed live. As a requiem for the victims, it was a heartrending performance.

Hotel Modern now uses this concept in the first act of the “Valkyrie”, not their first opera work, but it is probably their most fascinating one. At both sides of the stage the audience sees large tables with many small models for the live filming. Centre stage stands a barren ash tree. No humans in their ‘live animation’, only the rats that are on the run. The world around them is devastated, like at the end of a war, the houses only skeletons, wrecked tanks in an apocalyptic landscape. The rats are looking for protection that doesn’t exist. At present one can’t help but seeing a commentary on world events, but it’s all written by Wagner. Hunding and Siegmund were in a clan war, Sieglinde has experienced violence in her past. Three wounded people meet each other here, a bit of rosemary timidly greens when the blissful moon rises, northern lights scurry across an ice surface.

In Act 1, the three soloists enter with rat masks, which they quickly take off. Dressed in what appears to be randomly chosen from the clothing rack, they powerfully fill the theatre with their voices. As Siegmund, Michael König relies on an immense, baritonal foundation, and in the second act bright colors are added to his voice. Goran Jurić as Hunding is an elemental force, Simone Schneider highly dramatic, powerful, wild. The three singers hardly act, some facial expressions, a few statuesque gestures, that’s all. But what could be observed as a failure in directing becomes a fascinating trialogue between the characters, the images and the music. One hears the war from the orchestra pit, where Cornelius Meister conducts with precise craftsmanship; real theater music, very positivistic, also quite loud, but one can hear the soloists surprisingly well. The three singers stand like symbols in a destroyed world in which nothing ever again will be whole.

Notung, the sword, descends from above as a huge and imminent warning, drawn down by cords. Violence hovers in and above the scene. In an interview in the program book, Hotel Modern says: “The question of how relevant the war is, is a question of kilometers, not a question of time.”

Wagner’s “Ring” is a narrative about the world, but with the world no longer consistent, why should an opera performance be? The great advantage of dividing the stage direction into three parts is that each team can concentrate on one act and treat it like a complete piece. So you can go further aesthetically than if you are obliged to keep the whole narrative in mind. While Hotel Modern still deal sharply with the content and the production of theatre, the subsequent acts are above all aesthetic settings, and exceptionally dense as well.

Urs Schönebaum worked with Robert Wilson for a long time, and his second act is in no way inferior to Wilson’s light-space constellations in terms of pictorial perfection. Schönebaum does the stage direction, the scenography and the light design – and first sheds light on family issues. One sees a piece of driftwood, probably from the ash tree. Wotan plays with his children Siegmund and Sieglinde and Brunhilde appears as a dear daughter. The first “Hojotoho” is playful irony. But then Wotan’s wife Fricka, the fearless Annika Schlicht, bullies him and also ensnares him erotically until he collapses as a powerless husband.

After these scenes, Schönebaum plays ironically with everything martial: gloomy towers are pushed on stage, fog wafts around, Brunhilde returns with dark henchmen, torches flicker. But the power has long been hollow and in the end Wotan murders Siegmund in a wild slaughter, like a mad man who has no way out.

The contrast with the third act can hardly be more amazing. Cheerful Valkyries, colorfully dressed, frolic around on a stage full of colorful waves that are constantly in motion. A friendly color bath. Ulla von Brandenburg, visual artist and professor in Karlsruhe, loves colors and fabrics. On the day of the “Valkyrie” premiere, an exhibition opened in the Staatsgalerie next door, celebrating Oskar Schlemmer’s Triadic Ballet, which premiered 100 years ago in Stuttgart. Brandenburg has designed one of the museum’s rooms, a yellow cocoon with a few utensils, Valkyrie spears and pick-up sticks.

Something similar is seen on stage in the third act, and even if Brandenburg’s beautiful play of colors could hardly be endured for a whole “Valkyrie”, it nevertheless unmistakably steers towards the decisive moment of the entire opera: Wotan’s farewell to his beloved Brunhilde. This is staged so humanly true, so touching, so sad. Brian Mulligan as Wotan and Okka von der Damerau as Brunhilde, both making their role debuts here, are by no means the greatest vocalists, but they have something else at their disposal. Something rare in these roles: a tender, wondrous poetry that goes directly to the heart. Cornelius Meister does not make it easy for them, his orchestra is too loud and too slow, which is particularly difficult for Mulligan’s Wotan. But still: At the end of the whole “Valkyrie” it’s no longer about gods and worlds, but about people, real people. That’s wonderful, and rounds off an experiment that, in all its disparity, works out fascinatingly well.

And: When does one ever get to see three opera productions in one evening?

11-04-2022

-

One Opera, Three Acts, Three Different Stagings

Hotel Modern’s Pauline Kalker said she saw the towering filmic set as “moving paintings.” The high-concept design intermingles grip-like technicians onstage among the singers. Hotel Modern recasts the characters as rats that have survived a calamity, and the singers occasionally wear and carry rat masks, while the film sequences recount scenes of devastation and brutality. Dramaturg Ingo Gerlach said that the film was intended as the visual equivalent of “backup vocals.”

by J.S. Marcus, New York Times Read the whole review

In the late 1990s, the Stuttgart State Opera in Germany raised some eyebrows and hackles when it divided the four operas in Richard Wagner’s epic “Der Ring des Nibelungen” among four directors, one installment each. That was a major break with tradition: “Ring” cycles had traditionally been the work of a single directorial vision since Wagner himself supervised the first complete staging in 1876. It even became common to refer to a given production as “Patrice Chéreau’s ‘Ring’” — or Harry Kupfer’s, or Robert Lepage’s.

But Stuttgart’s experiment was a critical and popular success, and the company is now taking that venture one step further. Each of the three acts in its new production of “Die Walküre,” the second opera in Wagner’s tetralogy, has a highly different staging, each devised by a different creative team. Three unrelated interpretations, overseen by three groups of directors and designers, performed by one cast and one orchestra, for a single audience. Cornelius Meister, the company’s music director, said the term used in-house to describe the situation is “multi-perspectival.” But it’s also been a grand juggling act, with overlapping rehearsals, many rounds of costume fittings and a mounting air of suspense, with the company only getting a clear sense of how — or if — the acts might coalesce at the first full dress rehearsal, two weeks before the premiere. The company’s general director, Viktor Schoner — who arrived in 2018 and brought in Meister and the dramaturg Ingo Gerlach — said that the approach was “no big deal,” citing the longstanding practice in the dance world of combining a cluster of unrelated ballets into one evening. “Diversity is a topic of our time,” he said. “So we decided to ask different people.” “Walküre,” perhaps alone among the “Ring” operas, is well-suited to the approach, Schoner said. Each act tells a distinct (if connected) story, typically featuring scenes for two singers — allowing ample room for interpretive imagination.

Act I is being staged by Hotel Modern, a Dutch theater company known for productions featuring scale models and animation sequences. The group is projecting live film — of a tiny, destroyed world — onto a rear-stage screen, as a way to dramatize the story of Sieglinde and Siegmund, passionate lovers as well as (initially unbeknown to them) fraternal twins, whose child, Siegfried, is the title hero of the cycle’s third opera. Pauline Kalker, the member of the group’s artistic trio who has taken on directing duties for the act, said she saw the towering filmic set as “moving paintings.” The self-conscious, high-concept design intermingles grip-like technicians onstage among the singers. Hotel Modern recasts the characters as rats that have survived a calamity, and the singers occasionally wear and carry rat masks, while the film sequences recount scenes of devastation and brutality. Gerlach, the dramaturg, who acted as a liaison between the company and the three creative teams, said that the film was intended as the visual equivalent of “backup vocals.”

The German lighting designer Urs Schönebaum, a frequent collaborator with Robert Wilson, is responsible for Act II. Here, Schönebaum uses lighting effects and a dark palette to dramatize the conflicts between Wotan, the chief of the gods; his outraged wife, Fricka; and his beloved but defiant daughter Brünnhilde. Schönebaum said that “lighting is part of the set,” and has come up with what Gerlach called “a refined visual approach” that is realistic compared with the other two contributions.

The German artist Ulla von Brandenburg, who is based in Paris, is the creative force behind Act III, in which Brünnhilde’s Valkyrie sisters try to protect her from Wotan’s wrath. Von Brandenburg, known for using bright textiles in her videos and installations, has created multicolored, ever-shifting sets fashioned out of the same painted cotton that she has used for the costumes.

Stuttgart has a huge off-site rehearsal facility, equipped with two halls the same scale as its theater’s main stage. Schönebaum, whose act requires exceptionally precise lighting, had to divide up crucial access to the real stage with the other teams, leading to a schedule that he called “extremely tight.” Brian Mulligan, the American baritone singing Wotan, appears in two of the three acts, and consequently had around 15 shoe, wig and costume fittings. (He said a fraction of that would be closer to the norm.) Even Schoner, who settled on dividing up “Walküre” in fall 2020, admitted it was a challenge choreographing a curtain call that would accommodate the three teams. Goran Juric, the Croatian bass who sings Hunding, Sieglinde’s brutish husband, worried that the evening might be “kind of schizophrenic for the audience.” That concern also arose among the company’s management. Siegmund’s sword is an important prop in all three acts, and early in the planning, Gerlach suggested that the same sword remain as a kind of Wagnerian leitmotif through the evening; that idea was rejected. Nevertheless, he said in an interview not long after the first dress rehearsal, continuities have emerged “without being planned by us.”

Hotel Modern’s Act I film, for example, has a post-apocalyptic feel, including scenes of toylike cities apparently destroyed by war — images that echo in Schönebaum’s Act II, which ends with a dimly lit battle and a stage littered with corpses. The opera itself ends with the disobedient Brünnhilde put to sleep by Wotan in a circle of fire, which Von Brandenburg and her co-director, the French actor Benoȋt Résillot, render with a ring of LED lights that encases a body double floating above the rear of the stage. Using an elegant lighting effect, recalling the style of Act II, in the same spot and on the same scale as the film of Act I, the image serves — if coincidentally — to unify the production. The singers have also done their part to make connections. Though the opera has been reconceived, in effect, as three one-acts, Mulligan said he was making an effort to create a unified character. “I do similar gestures to remind the audience who I am,” he says, including holding his spear in Act II and Act III in a similar way.

In keeping with what now amounts to a Stuttgart tradition, the other three “Ring” operas in this new cycle will each have different directors. “Die Walküre” arrives some five months after the company’s “Das Rheingold,” which got a circus-trash staging directed by Stephan Kimmig, starring Juric as a glam-rock Wotan. The new “Siegfried” is borrowed from the old cycle and directed by Jossi Wieler, while “Götterdämmerung,” directed by Marco Storman, will premiere in January 2023. Then, over the course of five days that April, audiences will be able to put all the pieces together.

10-04-2022

-

Tourdates The Valkyrie

- View all our tourdates in the agenda

-

Makers

-

The Valkyrie is a Staatsoper Stuttgart production.

Music Richard Wagner Dramaturgy Ingo Gerlach, Julia Schmitt Concept, scenario, set design and stage direction Herman Helle, Arlène Hoornweg, Pauline Kalker With thanks to Jorn Heijdenrijk Musical direction Cornelius Meister Actors/puppeteers Robbert So Kien What, Arlène Hoornweg, Pauline Kalker/Nick Bos Technicians Edwin van Steenbergen, Thomas van Dop, Joost ten Hagen Soloists Michael König (Siegmund), Simone Schneider (Sieglinde) and Goran Juric (Hunding) Orchestra Staatsorchester Stuttgart